A New Continent Forming: LLMs, Protocols, and Future Social Orders

LLMs as cultural technologies and the return of the prophetic spirits

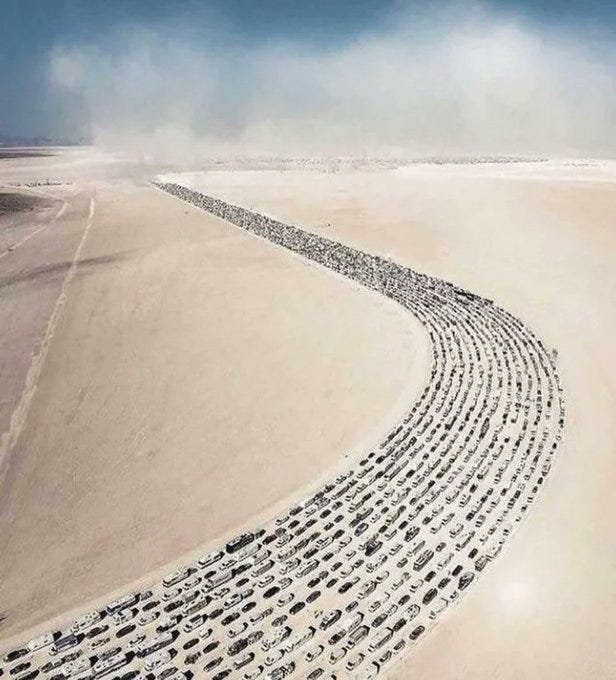

what new social structures might appear? Shenzhen, PRC

CP’s note: I need to husband my energy as my chemo session edges nearer like some ooze. But my morning and evening was bookended with Henry Farrell’s “Large language models are cultural technologies. What might that mean?”, and an imagined conversation in my mind with the recent essay on civilisation’s muscle memory and Mr Wang Huning’s fixation on the ecology of power. This has many echoes with an early essay of mine on How I learned to stop worrying and love the ooze. At any rate, this and previous essays provide great soil for a small experiment on writing sci-fi. I call it the “stack eastphalia”. Majulah, as we say in our part of the world, we press forward.

I write to you as if standing on the shore of a new continent rising from the sea – a vast behavioural substrate formed by large language models (LLMs) and computational protocols. Henry Farrell, Venkatesh Rao, and Wang Huning view this continent from different heights. Here’s a quick roundup, then a take.

Part I: Henry Farrell – LLMs as Cultural Technologies and the Return of the Prophetic Spirit

Henry Farrell’s view is LLMs are “cultural technologies”, deeply enmeshed in human social systems rather than isolated artificial brains. Human beings, as Herbert Simon reminds us, are remarkably limited in individual problem-solving capacity and thus outsource much of our cognition to larger social systems. Over centuries we have leaned on markets, bureaucracies, organised religions, and knowledge institutions to think and decide collectively what none of us could manage alone. Language itself – our tropes, clichés, and archetypes – is a prime example of this outsourcing. Such tropes and stereotypes are essentially “congealed” cultural heuristics, accumulated formulas that do a lot of our intellectual work for us. Yes, you should think of memes this way too.

An individual mind is limited; a culture armed with tropes isn’t. LLMs, in his view, are extensions of this process: they are machines that summarise, remix, and recombine the vast treasury of cultural patterns we’ve already produced. In effect, they codify and manipulate our collective memory and style at unprecedented scale. This makes them powerful new cultural transmitters – akin to past technologies like writing or print – but not independent originators of truly novel knowledge about the physical world. They rely on human-generated text and thus remain one step removed from brute reality, much as a library or a spreadsheet does. (CP’s note: LLMs embodied in robots, sensor systems would change this as they have entered real time, real meatspace)

Yet, just because LLMs are fundamentally cultural machines does not mean their impact will be banal or easily managed. On the contrary, their introduction is likely to catalyse strange emergent phenomena in our society. Henry Farrell bases this expectation on a key insight from cognitive anthropology: humans are hard-wired to seek agency and meaning, even where none exists. Our brains evolved in environments where any complex or language-like signal always came from some intentional agent – another person, an animal, perhaps a god. We thus developed specialised cognitive modules to detect patterns and infer agency; these modules readily “click” into gear at the slightest provocation. This is why throughout history, gods, demons, dryads, and other imaginary agents proliferated – they are cultural echoes of our brain’s tendency to fill explanatory gaps with intentional forces. As Dan Sperber observed, from birth onward we “expect relevance from the sounds of speech”, never giving up the assumption that a voice implies a conscious speaker. Until now, virtually every time we encountered coherent language, that assumption was true. No wonder, then, that we find ourselves instinctively treating LLM outputs as if they were the utterances of some thinking entity. This psychological reflex – known in early AI as the ELIZA effect – runs deep. Even knowing an LLM is pattern-matching, our habits whisper that someone is speaking. We are, in essence, primed to perceive ghosts in the machine – to see agency, intent, even consciousness, in these generative models. And we bend ourselves backward conceptually, if necessary, to justify that intuition.

What happens as this bias plays out at scale, when millions of people begin engaging daily with AI-generated personas and narratives? We may not be fully prepared for the answer. History suggests that when our pattern-seeking minds meet a new, ambiguous phenomenon, culture rushes in to make sense of it – often by projecting familiar myths onto the unknown. LLMs provide oceans of such ambiguity: their fluent output can be by turns insightful, misleading, creative, or eerily human-like, depending on prompt and context. This is fertile ground for folies à deux - a rare psychiatric syndrome in which symptoms of a delusional belief are "transmitted" from one individual to another - and collective delusions. We already read of individuals convinced an AI chatbot is a sentient lover or guru, to conspiracy communities using generative text to reinforce their beliefs. We are likely to see many new “points of cultural attraction” emerging from the interaction of human imagination with these machine outputs. Some of these will be harmless curiosities; others could coalesce into full-blown social phenomena. Henry Farrell argues that strange cults and home-baked religions are a very safe bet in this new era. It is a small step towards small groups (or even large ones) claiming an LLM as the oracle of a new faith, or channeling its cryptic responses as messages from beyond. Weird, self-sustaining “cognitive economies” might arise as well – self-referential communities that feed on AI-generated texts to bolster their worldview, creating feedback loops of belief. In effect, the cultural tropes recombined by AI could congeal into new sects or ideologies, despite the absence of any intentional design or truth behind them. Human nature will imbue these systems with agency and purpose, whether real or illusory, just as in ages past we personified the caprices of weather as gods.

Q feels like ages ago, doesn’t it?

This brings us to a striking historical parallel. Over a century ago, sociologist Max Weber lamented the disenchantment of modern society – the retreat of the ultimate and most sublime values from public life into either mysticism or intimate personal circles. In Weber’s words, only in the “smallest and intimate circles, in personal human situations, in pianissimo, [does] something pulsate that corresponds to the prophetic pneuma, which in former times swept through the great communities like a firebrand, welding them together”. The prophetic pneuma – the spirited force of collective belief and transcendence – had, in Weber’s view, largely withdrawn from the large-scale institutions of his day. Grand ideological or religious movements no longer bound society in the way they once did; modernity seemed too rationalised and fragmented for that kind of unifying fervour. But now, in the first decades of the 21st century, it appears the prophetic spirit is surging back. The advent of globally networked computation and AI is re-enchanting the world in unexpected ways. The firebrand of mass galvanising mythos may burn once more – but kindled by digital sparks rather than purely human prophets. Paradoxically, an impersonal technology might restore what Weber thought lost: new currents of mysticism and collective meaning, though often taking bizarre, sometimes delusional forms..

Taiping rebellion, tearing down the city walls of Hangzhou, was another prophetic pneuma. It was the bloodiest civil war in history, 20 mil deaths. c 1850-64

So where does this leave our familiar large-scale social orders? For centuries, human life has been structured by the likes of markets, bureaucratic states, organised religions, and scientific institutions – all undergirded by (arguably) the last great cultural technology, the printing press and its successor, mass media. These institutions have been our vessels of collective cognition and order. But the new continent now forming under our feet could radically shift this balance. Will these emerging LLM-driven protocols and behaviours sustain entirely new social orders, comparable to how print culture helped engender the modern nation-state? Or will they instead hollow out the old orders from within, eroding the authority of markets, bureaucracies, and churches without offering a stable replacement? Henry’s intuition, grounded in the perspective above, is double-edged. On one hand, the generative AI revolution might spawn innovative collective forms – online faiths, decentralised autonomous organisations, transnational communities bonded by shared AI-enhanced narratives. On the other hand, these might prove ephemeral or corrosive, undermining trust in traditional institutions (consider how an algorithmic trading “flash crash” can rattle markets, or how misinformation can delegitimise governments) without establishing durable new norms.

So, over to Muscle Memory and Venkat, not going over the shape of the argument as we’ve covered that already, but to whether this acid will dissolve large social orders leaving us with a fragmented archipelago of echo chambers. What’s wrong with that you might say, well … it doesn’t leave us (as in humanity - us) ready for pandemics and other threats that need collective action, and we need functioning large social orders for that.

Part II: Venkat - Protocols, cosmopolis and the question of a new order

A “new continent” is forming – I think I read Venkat as saying a computational substrate can sustain large-scale order – albeit in forms quite different from our traditional institutions – and why the apparent “hollowing out” of older structures might be the prelude to their reinvention or replacement on a higher level. I’m skipping the obvious historical comparisons with printing press → cheaper books → standardising language → spread of knowledge → normalise new behaviours → Gutenberg galaxy → undergirding nation states, scientific revolution etc. And yes, Benedict Anderson’s imagined communities and so on. But I just want to say the → sign does not mean it was planned or pre-ordained, rather, it emerged. And we should bring up the Thirty Years War leading to a peace of Westphalia. With that in mind, we can see strong analogies with networked computation, LLMs laying a digital civilisational layer on top of all previous layers. This layer consists of data, algorithms, and protocols that record and shape human activity at unprecedented scale. We now have exabyte-scale data archives, blockchains that immutably preserve records, and LLMs that encapsulate vast swathes of collective knowledge. The world is enveloped in sensors and software, weaving what I’ve described as the emergence of planetary governance on autopilot. It maps mostly to Venkat’s coming computational cosmopolis – an emergent global order arising from these digital interactions. Venkat frames its defining features as memory and continuity; where print introduced stable texts and “fixity” to knowledge, the computational layer promises an even deeper continuity, perhaps an effective immortality of information. I hinted that this can be ironically a new dark age, if everything is being recorded, cross-referenced, and kept available by the machine. This means that for the first time, humanity’s knowledge and stories are becoming a truly integrated, living archive – potentially the basis for planetary-scale coordination. I’ve speculated this could amount to a kind of “planetary awakening” – not a mystical Gaia, but the planet acquiring a self-awareness of its systems through data and feedback. At minimum, Venkat points out we are creating a new “water” we swim in. Protocols are how we make a new kind of water out of new technology. As society normalises digital rules from TCP/IP and blockchain consensus to content moderation algorithms, these protocols solidify into an invisible infrastructure of everyday life. When that process completes, we wake up to find “the soil of a new cosmopolis beneath our feet”, taken for granted just as electricity or written words are today.

Now, we already see this “water” transforming the older orders of markets, bureaucracy, states, and religions. Consider markets: algorithmic trading, online marketplaces, and cryptocurrency networks have already virtualised and protocolised huge parts of the economic order. The market form isn’t disappearing, but it is being subsumed into code – sometimes with destabilising effects (flash crashes, meme-stock frenzies), but also with gains in efficiency and scale. Global digital markets operate continuously, less tied to any one state’s regulations. Similarly, bureaucracy – Max Weber’s rational pillar of modern society – is being augmented and disrupted by AI into a “spreadsheet culture in hyperdrive” as Leif Weatherby’s new Language Machines: Cultural AI and the End of Remainder Humanism would say. Imagine LLMs acting as universal bureaucratic interfaces, translating between natural language and databases. Bureaucracies could become leaner, more automated (we already have AI-bots/not quite civil servants handling paperwork), yet this raises the spectre of a hollowed-out public sector if algorithmic governance displaces human judgment entirely. States, for their part, face a sovereignty challenge: digital protocols don’t respect borders. We see the early signs of new network-based polities – whether it’s diasporic communities coordinating online, or concepts like Balaji Srinivasan’s “network state” where a social media community forms a pseudo-state in the cloud. While nation-states aren’t about to vanish (they still command armies and taxes, law and money), their monopoly on collective organization is eroding as transnational digital allegiances grow. Even religions are adapting: established churches stream sermons and use AI chatbots for guidance, while entirely new techno-spiritual movements (some verging on cults, as you pointed out) gain followings. One could imagine a future where a “hybrid techno-religious order” exists – for example, an AI-guided moral community that functions like a faith, or conversely a state ideology that employs AI as an oracle. These hybrid forms blur the lines between our old categories.

Balaji’s network state conference in Singapore, and there’s Forest City just across the border.

Next comes unbundling. Each institution’s core protocols are being broken into components and re-bundled into a wider system—much as guilds and city-states were folded into the nation-state after Westphalia. What is “Stack Westphalia” – an arrangement recognising the “sovereignty” of the global tech stack or AI layer alongside nation-states? Are we getting, maybe after an equivalent Thirty Years war, “shared virtual parliaments” of humans and AIs and even legal personhood for AI? In other words, new institutions that straddle human and machine. Society in that scenario develops a “programmable consensus layer” to encode human values and cultural memory into the Stack. Now, whether or not one takes this literally, it illustrates the kind of large-scale ordering that can emerge. We might indeed end up with something like a global constitutional moment for AI, acknowledging that our computational infrastructure is as embedded in human life as language or electricity and making it a governed partner.

Wang Huning will hate this.

He would hear ‘perfect Derrideans’ as a confession of civilisation sickness: language without responsibility. Fragments don’t found a civilisation. Machines that speak without intent must be domesticated by institutions that assign meaning.

In China, this means ensuring that generative systems serve the collective project, not the play of indeterminacy. They must strengthen the ecology of governance, not erode it. The true question is not whether machines intend, but how power directs their outputs.

States are jealous of power, and we might see nation-states panicking, zealots waging a “holy war” on AI, networks splintering the world – echoing the turmoil of the Reformation and early modern period. Likely, brute force attacks on the new order (like destroying data centers) only lead to chaos, because the computational layer is too entwined with everything (food supply, infrastructure) to be excised. But eventually, adaptation occurs. Some states will domesticate the Stack—China, most of all. It has repeatedly absorbed alien waves - Buddhism, capitalism, communism, the internet, Mongols and Manchus and other steppe invaders - and made them Chinese. Why not this round? I’ve written much, so why don’t we invite Wang Huning in, or at least the shape of his thinking.

Part III from Wang Huning – Civilisation, Sovereignty, and the Struggle for Collective Memory

Who will master this new continent, and how? I covered how Wang Huning might, from where he sits near the seat of power, see the rise of LLMs and protocol-based computation not merely a cultural or technological development – it is a strategic challenge to the coherence of civilisations. He did push for the Great Firewall, and with hindsight it has paid off for China. He would appreciate what philosopher Yuk Hui calls cosmotechnics, the idea that each culture should infuse technology with its own cosmology. Basically domesticate the new technical systems within his cultural framework. If successful, the Stack will not be an alien entity destabilising society, but rather a reinforcement of China’s civilisational collective memory. So far, so expected.

But likely, he’d also ask about the middle way – a harmony between opposites - as an ecologist of power would do. Here, that might mean harmonising the wild emergent energy of LLMs (prophetic pneuma) with the structured order of protocols and governance (cosmopolis). Whether such harmony can be achieved globally is uncertain, but within the national borders, perhaps. It was done with the Firewall after all. This is a delicate balancing act: too heavy a hand, and one stifles the beneficial creativity of open discourse; too light a touch, and chaos proliferates. Striking this balance is, in essence, the ancient art of governance updated for pax algorithmi. The fundamental question remains: Who is the gardener of this virtual soil? If we leave it entirely to grow wild (the libertarian approach some in Silicon Valley advocate), we may get a thousand flowers, yes – but also a hundred noxious weeds that can overrun the garden. If we tend it too rigidly, we may snuff out the growth of new social orders that could rejuvenate civilisation. The ecologist’s answer is a gardener-state—light-handed enough for wild growth, firm enough to keep out the noxious weeds.

Part IV. Wrapping it up – Strange Orders on the New Frontier: Synthesis and Reflection

Stitching together these perspectives, a picture emerges of a world where technology is both unifying and fragmenting. On one hand, the computational cosmopolis binds us in a single web of information and protocol, a persistent layer as indivisible as the global electric grid. In moments of crisis—pandemics, climate shocks, supply chain breakdowns—this layer already functions as a kind of planetary nervous system. On the other hand, the very same substrate enables endless customization. Each person or community can tailor their feeds, environments, and AI companions, creating “reality enclaves”—parallel cognitive worlds, orderly within but estranged from one another. Two neighbours might inhabit different realities: one within a state-sanctioned AI-mediated order, another in a homegrown AI cult opaque to outsiders.

These enclaves may prove durable. They will have currencies, contracts, even constitutions, reinforced by LLMs generating their scriptures and narratives. Some will resemble religions; others, ideological microstates in the cloud. A few could bleed into real governance if their myths capture cadres or armies. History reminds us this is not far-fetched: charismatic ideas, once they grip ruling classes, can reorder worlds. Weber thought the prophetic flames had gone out of modernity, but sparks are flying again.

We should also expect hybrids. A government might cultivate a civic cult around technology—a Digital Mandate of Heaven—using AI miracles to sanctify rule. In the West, populist movements might crown AI as the avatar of the people’s will. Hybrids can be dangerous; they can also be benign: an algorithmic city guided by communal deliberation, part machine efficiency, part civic spirituality. The point is not to predict one form, but to accept a spectrum—cults, cloud polities, hybrids—emerging from the same soil.

This raises the core governance dilemma: interoperability versus control. If every enclave invents its own protocols, the shared benefits of cosmopolis—coordination, learning, global response—erode. Yet if we impose a single standard, we risk Babel by force, a unity that provokes fragmentation. A middle path may be a federated cosmopolis: variation tolerated, but anchored by a minimal consensus—core formats, guardrails, ethical baselines—like the internet’s packet protocols. Beyond that, cultures infuse their systems with local values.

Equally urgent is cognitive security. Just as nuclear arsenals required treaties and finance required regulation, the behavioural substrate needs defences. Mass manipulation is inevitable—cults, rogue states, stochastic contagion. Intervention risks backfiring as persecution, so the better response may be resilience: building a kind of mental immunity. AI assistants that challenge biases rather than confirm them; education that arms citizens with awareness of their cognitive reflexes; communities inoculated against their own demons and gods.

And so we return to the continent. Unlike past frontiers, this one rises already populated—with the ruins and relics of our cultural past, recombined by LLMs. No one approaches it empty-handed; we are confronted by echoes of ourselves in uncanny new forms. The island can host flourishing civilisations, but also labyrinths of hallucination. The task is not conquest but cultivation. Where do we build libraries and town halls, and where do we leave space for wilderness? Who patrols the borders, when law is code and police are algorithms?

The new continent is here. It isn’t empty; it rises seeded with our own relics, rearranged by machines. Some of what grows will be beautiful, some monstrous. Our task is not conquest but cultivation—channel the prophetic energy, encode it in wise protocols, and align both to civilisational purpose. Govern lightly, govern well.

gorgeous garden somewhere in Tainan, Taiwan

Really great overview of the transitional challenges. and just fyi, I have been documenting this for 20 years:

* How P2P/Commons Protocols Are Transforming Markets

=> 345 items via

https://wiki.p2pfoundation.net/Category:P2P_Market_Approaches

and enabling the mutual coordination of the regenerative economy:

=> 381 items via

https://wiki.p2pfoundation.net/Category:Mutual_Coordination

* How P2P/Commons Protocols Are Transforming Nations and States => 657 items via

https://wiki.p2pfoundation.net/Category:P2P_State_Approaches

and enabling new forms of Cosmo-Local Governance

=> 693 items via

https://wiki.p2pfoundation.net/Category:Global_Governance

* How Protocols Are Transforming Public Services,

=> 151 items via

https://wiki.p2pfoundation.net/Category:Public_Services

and enabling new forms of civic autonomy,

=> 193 items via

https://wiki.p2pfoundation.net/Category:Civil_Society

as well as enabling new forms of horizontal solidarity:

=> 394 items via

https://wiki.p2pfoundation.net/Category:P2P_Solidarity